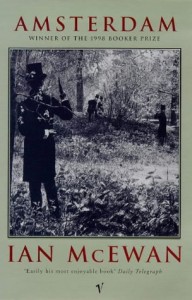

#14 Amsterdam by Ian McEwan

I’m really not doing well with this book review project, am I?

I’m really not doing well with this book review project, am I?

But I have my reasons – I published a novel with Amazon, at the same time as my wonderful agent retired from the business, and my new agent (also wonderful, am I not a lucky writer?) is trying to get said novel in some way transferred from one agency to another via a process that appears to involve slaughtering virgins, it’s so demanding. And my husband (or OH for those who read the gardening books) has recently had a major operation to deal with cancer … which has turned out to also be rather more complicated than expected. So life has narrowed to a round of meeting small deadlines, travelling to hospitals, and – in between – checking myself on Amazon only to find that my novel is endlessly unavailable, which somewhat feels like a heavy-handed metaphor for life!

Onward. I’m favouring slight books – at least in terms of word count, as my attention span is short, my temper shorter and my bag tends to always contain T-shirts, packed meals and soft drinks for OH (he finds hospital food frankly inedible) so skinny books are easy to fit in both physically and mentally. Here’s the latest.

In a rather snippy Guardian review, it was suggested that Amsterdam winning the Booker Prize was McEwan’s misfortune rather than his luck. I am inclined to agree. McEwan’s strength is the cool way he enters characters, like a scalpel, laying bare the workings of their lives by revealing whatever mutation, aberration or lack has led to their ultimate consequence. In Amsterdam he does this a little too much, there is nobody and nothing to love and therefore no reason to give a damn what happens to anybody.

The only appealing character is dead when the novel opens, in fact we are at her funeral. Molly, the onetime lover of both Clive and Vernon, is being celebrated by all her other lovers and her hideous death, prolonged, insane and powerless, is the first subject we hear Clive and Vernon discuss. They agree that should such a thing ever happen to each of them, they would wish to be euthanised, and so the ham-fisted plot lumbers into action. The focus for their venom is George, rich but dull publisher who was Molly’s husband at the end, and who kept both of them away from her so he could oversee her terrible death and possess her in her illness as he never did in life.

I won’t bother with spoilers, the book is small enough for anybody to tackle (although they won’t necessarily feel they haven’t wasted reading time) and there are some glorious moments in it. In particular Vernon, as a newspaper editor, grapples with the voracious demands for sensation from both readers and proprietors that in 1998 foreshadows the genuine horrors revealed by phone tapping. His downfall, prompted by the way he’s handled some red-hot photos of a senior politician in drag, is a piece of glorious writing, but the glory is somewhat blunted by the simple impossibility of Vernon’s having sat on the photographs not for just days, but weeks. Even in 1998 this would have been daft. There is no internet in this book – no sense of the pressure, even then for instant news – 1998 was the year of the Clinton impeachment, and it was all over what passed for the www those days but McEwan gives no scope to that force for instant gratification, instead Vernon has the power to sit on a great story like a good hand of cards, without any sense that the world is looking over his shoulder or rummaging through the rest of the pack to work out what he’s got.

Again and again in this book, the cleverness of the plot slides us past the implausibility of the events. Clive’s struggle to write a truly fresh yet forceful symphony for the millennium is a nice conceit – for those with the Millennium Dome experience in their lifelines (old people, in other words!) it’s a beautifully rendered version of the good driving out the best, although in this case the mechanism that actually drives out the crucial musical theme that would have saved Clive’s bacon is, in classic McEwan style, a rape. It’s the opening brutalities that Clive observes, as he’s working on the opening motifs of his symphony and he chooses to move away from the building violence, leaving the woman to her fate, so he can concentrate on his inner creative processes.

In both cases, Clive and Vernon are condemned by their own pusillanimity – Vernon does not strike fast enough, Clive refuses to strike at all, for fear of being struck. How their fates find them is more laboured than I’ve come to expect from a writer of McEwan’s skills, and it’s only satisfying because we really don’t want these men to prosper from their shallow self-serving decisions. They don’t, but oddly, the man who does is George – so any moral satisfaction from their collapses is destroyed by the fact that the narrowest, least courageous and most boring character in the book appears to win everything at the end. I found this profoundly unsatisfying.

Amsterdam is definitely not McEwan’s best book – those who began with his first work, The Cement Garden, will find this novel too comfortable, and those who began with Atonement, his most famous work, will find this too thin.

2 Comments

Rebekah

30th May 2015Your last paragraph says it all, especially as I’m a fan of his early work. Have been thinking of you and those Tales days. Sending you all my best for summer of good fortune for you and your partner.

Kay Sexton

1st June 2015Thanks Rebekah, it was fun doing the Tales readings, wasn’t it? I hope we’re going to have a summer of good fortune too, but first we have to get a summer …