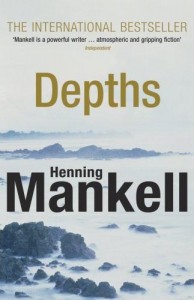

#18 Depths, by Henning Mankell

There seems to be a Scandinavian preoccupation with measurement. In Peter Hoeg’s novel, Borderliners, it is the measurement of time that is central to the narrative, in Depths, by Henning Mankell it is the distance between the surface of the ocean and the sea bed. Or at least, that’s how it begins.

There seems to be a Scandinavian preoccupation with measurement. In Peter Hoeg’s novel, Borderliners, it is the measurement of time that is central to the narrative, in Depths, by Henning Mankell it is the distance between the surface of the ocean and the sea bed. Or at least, that’s how it begins.

Lars Tobiasson-Svartman is a naval engineer whose job it is to measure depths – although in considering the novel I do believe the British word plumb is never used, an oddity that has just struck me. From the beginning we wonder about Lars Tobiasson- Svartman; when he arrives at his new posting he has already spent time finding out the one place on deck, theoretically, where he can be completely hidden. He confirms his theory in practice and then simply stands in his hiding place. Why does he need it? What does he plan to do with it?

The answer, which emerges slowly throughout the course of the book is, nothing. He is just the type of man who likes to have a place where he can observe unseen and for much of his life, that’s what he does. What happens in the other small fraction of his life is violence – some planned, some unplanned, some the inevitable outcome of a secretive and deceitful man, some random and unprovoked unpleasantness. Some isn’t even Lars Tobiasson-Svartman’s own behaviour – his wife Kristina Tacker boxes the servant girl’s ears for no good reason. But this violence is as necessary to him as the silence and space he seeks so compulsively. He is a man for whom women are enigmatic and in whom the normal aspects of life: runny noses, meowing cats, can provoke brutality.

As he explores the sea channels around the Swedish coast, testing to find a swifter passage for Swedish vessels at the outbreak of the Great War, he is shocked to find a young widow living on an uninhabited island. His wife, Kristina Tacker, vanishes from his mind to be replaced by Sara Fredrika, the hermit-like inhabitant of Halsskär.

In short order his obsession with Sara Fredrika requires him to become a killer, first of cats, then of men and he simply continues his fatal career, apparently baffled by both the women in his life and veering between them in a largely passive and underhanded way. As we learn more about him the somewhat heavy symbolism of his life is revealed. He has a sounding lead (made in Manchester) with which he measures hidden depths, but he also mentally measures distances between people, between his emotions and his actions and between his lies and reality. In the end, it is that final distance, between the duplicity that overwhelms him and his ability to understand his own actions, that destroys not just him but Kristina Tacker too.

There are notable aspects to this novel – not least the sometimes peculiar perspective of seeing an historical novel written from a viewpoint that is neither British not ‘other’ in the hideous catch-all phrase that defines (or fails to define) the perspective of peoples, genders and associations that are not those in power. The Swedish position, at the beginning of World War One and according to Mankell, is a schadenfreude-based approach that hopes Britain will be thoroughly humiliated by the Germans and Russians, not because the Germans or Russians are particularly popular but because the British are profoundly unpopular. It’s a bit like walking past a room where somebody is doing an impression and then realising the unflattering mimicry is of your own characteristics.

Another impressive achievement is the containedness of Lars Tobiasson-Svartman who, for this reader at least, was a sympathetic character at the beginning. He is hard-working, dedicated, fastidious, solitary. His dislikes are wholly understandable; who hasn’t been offended by the eating, breathing or personal habits of others? Which of us isn’t occasionally furious (internally or externally) when affronted by the lazy or slovenly behaviour of our colleagues? But slowly, as the gyre tightens around Tobiasson-Svartman – which it does in an exact relation to the scope he is given to determine his own actions – we learn more about him and the more we learn, the more disquieting he becomes. Revelations of violence in the book grow in intensity and unpleasantness but because they are backstory, we have the unpleasant experience of revising our view of the protagonist and liking him less each time we discover one of his unsavoury actions. Still, throughout the narrative, this protagonist acts on others but is barely acted on himself. His impulses are created from his thinking, or even from the formlessness of impulse itself – his engagement with others is so limited that the closer he gets to somebody, the less he talks to them until his most intimate relationships are almost silent. He is at once believable and completely incomprehensible and this is a major success when killers are all too often caricatures.

Recent Comments