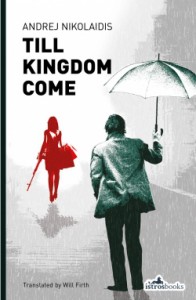

#19 Till Kingdom Come by Andrej Nikolaidis

I was of fered an opportunity to review this novel by somebody who knew of my love for thrillers, novels with abrupt changes of focus, and the work of Eastern European writers in general.

fered an opportunity to review this novel by somebody who knew of my love for thrillers, novels with abrupt changes of focus, and the work of Eastern European writers in general.

Let’s begin with that middle category – books with abrupt changes of focus. Two of my favourites, Peter Hoeg’s Miss Smilla’s Feeling for Snow and Mark Slouka’s The Visible World both encapsulate this approach in different ways – Hoeg’s novel takes a left turn into a kind of near science fiction whilst Slouka’s putative narrator vanishes entirely for most of the book. You either like this or you don’t – I’m a liker!

What it does require is two things of the reader and one from the writer – from the reader it demands a willingness to abandon the much vaunted narrative arc plus a degree of commitment to the process of reading and from the writer a ‘writerliness’ that allows him or her to transcend the point where the suspension of disbelief is threatened by the derailment of said arc. From my reading of Till Kingdom Come, I can’t quite tell if Nikolaidis has this or not, because works in translation can sometimes lack something of the writer’s innate prose style. A couple of clunkers early in the novel set my literary teeth on edge, which made it slightly harder for the novel to carry me round the sharp curve that the story takes.

The first clunker was on page 9. “Listen,” I said to him, “I see you get the idea of the free Cola from pizza delivery services, but if you think about it you”

I realise how absurd it is. Cola may go with pizza, but with cigarettes you need alcohol or coffee.”

He looked at me bluntly through the streams of sweat running down his face.

I can’t tell if that’s a translation error or a copy-editing one, but it jarred me, as did the second on page 25. Everything I had gained cost me a dearly. It wasn’t worth it.

I’m aware that this sounds nitpicking, especially from a writer who has found at least one typo in every one of her published books, but this novel is only 125 pages long, which makes egregious errors even more egregious – and where a writer is about to propel us through a series of blind bends into a completely different style of story, such apparently minor issues can send the reader into the crash barrier.

Setting aside my minor discontents, this novel is a miniature marvel; Kafka-esque in structure, delicious in ennui, full of little epigrams on futility and lyrical expositions of cynical or incompetent government in the Balkans, it’s a folk tale with drink, drugs and unscrupulous politicians. It opens Biblically – with a flood, and just when we’ve got used to our hero, drinking, smoking and pensively observing the physical, political and moral collapse of his home town, the narrative plunges into a criminal/espionage tale in which the arrival of a threatening great uncle reveals that the narrator’s grandmother was not his grandmother and that nothing he thought he knew about himself is real. We follow him as he sleepwalks (literally) across Europe, experiencing shocking revelations about his mother (a government hired contract killer, as far as we ever ascertain), and about a series of apparently unrelated murders ranging from the arsenic poisoning of a village worth of people (mainly men) who pissed off a female herbalist or her female acquaintances through to occult killings carried out across the world by a secret church.

During his hallucinogenic investigations, the narrator loses everything of value in his life and the novel ends with a story from the New York Times which describes the end of the world as an entropic decline in which ‘everything will be frozen, like a snapshot of one instant, forever.’

It’s a complex, sometimes dizzying and often abrupt set of transitions which ends with such an open-ended ‘conclusion’ that it doesn’t merit the term at all, but even so, Nikolaidis has pulled off the stunt for several reasons – first, his prose is lyrical and studded with such deliriously concrete images it reads like a police report of a crystal meth episode – the children’s paddling pool filled with bottles of booze being towed through the flood by a Trabant is a particularly delicious example. I adored, for example, the sentence spoken by the narrator’s secret love the melancholic Maria, ‘But sorrow is like the large intestine; everyone has one.’ Such lucid, poignant and unsentimental writing deserves a wide audience.

Second, the long tradition of conspiracy theory (like that explored in Umberto Eco’s The Prague Cemetery which I reviewed recently) has a substantial enough body of work for the reader to slide this work naturally into that context and master the slippery turns of narrative.

Overall I recommend the read – particularly if you like a book that challenges you on several levels. The wide-open ending might disappoint some readers but I found it exactly right for this strange tale of loss, ennui and conspiracy – if you like Milan Kundera and Kafka, this will definitely work for you!

Published by Istros Books, a press dedicated to the work of Balkan and South Eastern European writers in translation, this is a small but peculiarly attractive addition to the world of conspiracy theory literature, marrying as it does a polemical journalistic exposé of the failures of post Cold War Balkan states with a mad adventure into a world where nobody is who they seemed and almost everybody dies.

Recent Comments