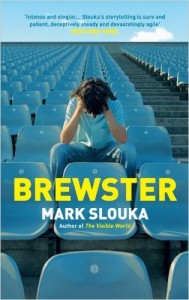

#20 Brewster by Mark Slouka

Many, many years ago, I wrote about ‘The Visible World’ and argued, somewhat contentiously I now think, that it was one of those novels that fails, but fails rather wonderfully. By ‘fail’ I mean that the reader, at the end of the novel, is left with a feeling of dissatisfaction about something (or somebody) instrumental to the workings of the book. In ‘The Visible World’ my concern was that the narrator was almost unnecessary, a device rather than a character. My further argument is that it doesn’t matter because the book fails so magnificently that its failure is more cogent than the kind of success that a more ‘regular’ novel might enjoy.

Many, many years ago, I wrote about ‘The Visible World’ and argued, somewhat contentiously I now think, that it was one of those novels that fails, but fails rather wonderfully. By ‘fail’ I mean that the reader, at the end of the novel, is left with a feeling of dissatisfaction about something (or somebody) instrumental to the workings of the book. In ‘The Visible World’ my concern was that the narrator was almost unnecessary, a device rather than a character. My further argument is that it doesn’t matter because the book fails so magnificently that its failure is more cogent than the kind of success that a more ‘regular’ novel might enjoy.

You know, reflecting on this process, one fifth of the way through my 100 reviews, I’m coming to the conclusion, somewhat to my surprise, that I’m a very tough reviewer. I don’t intend to be, and I am troubled by the idea that writers might find what I say about their work to be uncomfortable or even unkind because that’s not my intention. Perhaps I’m just rigorous – I’d like to think so, but looking back on that first review I wonder if I was unduly harsh because I loved ‘The Visible World’ and the book has remained with me ever since I first read it.

So … to Brewster. Set across the fracture line of the late 1960s and early 1970s when the happy hippy era gave way to a bleakly and swiftly consumerist period, often dubbed the ‘me’ decade. Nothing could be less true for the narrator of Brewster – Jon Mosher, whose parents have settled invisibly into American life after escaping the horrors of Europe’s treatment of Jews in the second world war. And nothing could be less true for his best friend and the hero of the book, Ray Cappicciano, whose family life, unlike Jon’s, is volatile and unpredictable. Together these young men fight both for and against their origins and they do so silently, bitterly and without any confidence they will succeed – the only saving grace for either of them, at the beginning, is that they have each other. Their friendship is based on the unspoken lack of love that they both experience when they open the front door and walk into what they call home. In Jon’s case it’s the tragic death of his older brother when still a small child that has crippled his family, rendering them stunned by loss and stunted by the experience.

What happens in Ray’s home emerges slowly through the narrative – a harrowing, horrible, and yet completely explicable process; take a man, give him a hideous war to live through, pour unlimited alcohol on those vile memories, put him in another uniform that protects him from exposure, in this case that of a policeman. Let the women he has children with leave him because of his violence. Let those children remain in his dubious care … this, we know, cannot end well.

This then, is the bony anatomy of the story. Ray’s little brother Gene, his girlfriend Karen – a relentlessly normal young woman – and Jon himself are drawn into the tightening spiral of Ray’s life, where he plays out the tough guy role because there is nothing else for him to do. Also in that circle is Frank, another schoolfriend who has acne, God and track team in his life. Jon and Frank become acquainted in the cafeteria of their High School where Ray joins them, very much on his own terms, with Karen on his arm. Jon is invited to join the running squad and his life changes as he finds a purpose that allows him to have reason for his anger and isolation as well as a challenge which he sorely needs to counteract his empty existence at home and school.

The four young people are desperate to escape Brewster, a dead end town where, according to Jon, it always seemed to be winter. Without giving anything away, the escape routes that they take are not what anybody would have expected.

Suffused with the universal violence of the Second World War and the Vietnam War, lost in the short-lived age of peace and love which reached Brewster only as the ‘children of God’ passing through in their sandals and ponchos, with Brewster as the ‘dead unmoving cog at the center of things, the pivot point, the pin in the tie-dye pinwheel. Watching the colors blur just made it worse’ Jon, Ray, Karen and Frank are unable to live on their own terms as the heavy hand of conscription, conformity and national interest falls over them, and as the broken, inadequate adults they call parents fail them all.

In some cases the failure is huge, Shakespearean, grand guignol, in others it is the small failure of imagination that has Frank grounded for an entire summer because he doesn’t want to teach Sunday School any more. In every case, this failure leads to a greater failure, the failure of potential, the failure to admit failure, the failure of nations, families and individuals to recognise their own inadequacy … and that failure leads to tragedy.

It is, for me, a masterwork. Stephen King meets Christopher Marlowe on the Field of Dreams. Broken bones of imagery poke through the icy grey experiences of the troubled teenagers, and Jon’s running career is not so much an escape as a rebellion – he runs not because he can but because as long as there is something, anything, to aim for, he can try not to look at the purposelessness of his life.

What makes this novel so masterly is that out of the inexorably tightening drama, the dark, cold, endless winter of poor towns, poor parenting and few choices, Slouka rips a redemptive ending, a thoughtful, powerful, sinewy portrait of hope for the future, based on tiny fragments of goodwill and individual bravery.

I am so glad that I was hard on ‘The Visible World’ as that allows me to be fulsome about ‘Brewster’. Read this book, it is bloody excellent!

Recent Comments