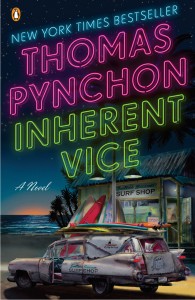

#25 Inherent Vice by Thomas Pynchon

I have always understood Pynchon to be inaccessible, so in choosing Inherent Vice as my first Pynchon I was deliberately opting for the most accessible of his novels. Perhaps it’s not at all representative – Gravity’s Rainbow is described as ‘sweeping’, ‘complex’, and even ‘mysterious’ – but Inherent Vice is more of a romp than I ever imagined.

I have always understood Pynchon to be inaccessible, so in choosing Inherent Vice as my first Pynchon I was deliberately opting for the most accessible of his novels. Perhaps it’s not at all representative – Gravity’s Rainbow is described as ‘sweeping’, ‘complex’, and even ‘mysterious’ – but Inherent Vice is more of a romp than I ever imagined.

Set as the sixties tip over into the entirely darker and less rewarding seventies, the novel’s protagonist, Doc Sportello travels through a cast of hundreds, mainly dopers and stoners, as part of his attempt to discover what has happened to his ex-girlfriend’s new lover who is married to a woman who might be trying to have him committed to an insane asylum before he can give away his fortune … it is only just no longer the sixties, after all.

Sportello claims to be a private detective but mainly seems to be a drifter around a beach in LA County where dopers and stoners, Hell’s Angels, property developers, whores, musicians and limo drivers interact in apparently random patterns that Doc must decipher. His main aids to detection seem to be smoking a lot of weed with the occasional excursion into acid to give him insights into his cases.

As the book advances, which it does by a series of elliptical plot developments, his private eye encounters become vignettes of the end of the hippy era. 1970 in Doc’s world is marked by the trial of Charles Manson and his acolytes for murder – a clear sign that the Age of Aquarius has become a literally bloody New Age. But despite the occasional reverie on the evils of capitalism, and some delicious random paranoia which Doc both catches and infects others with on his travels, there is nothing heavy about this novel. The intermittent appearance of Denis (rhymes with Penis) possibly the most clueless inhabitant of a deliberately clueless culture, can hardly count as light relief in a narrative that manages to remain light despite shoot-outs, police brutality and a sense of nostalgia for the earlier, kinder age that pervades not just Doc’s thinking, but the lives of many of the characters to which Pynchon introduces us.

The bleakest point in the novel is the final page, where Doc, with answers if no conclusions, finds himself driving on the freeway in fog, bumper to bumper with – it seems – the whole of LA, moving forward in synchrony into a blank future they are helpless to avoid. As a symbol of what America does to itself in the 1970s, it’s a fair statement, but in Doc’s mind it is also a love song to the American way of life – often mindless but always in motion and that too has an undeniable appeal which Pynchon nails effortlessly; American may be going nowhere, but it’s doing so in style.

I was carried along by the book, although aware of Doc’s many digressions and the lack of pace, or even anything like direction, a lot of the time. Pynchon evokes the era with such love, detail and sly humour that it was impossible for me to become annoyed at the lack of narrative drive. As for inaccessibility, I think I’ll have to try another Pynchon because this one was not just accessible but extremely palatable.

Recent Comments