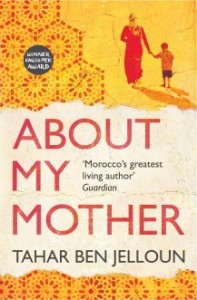

#30 About My Mother by Tahar Ben Jelloun

First and foremost, I am ashamed … only my thirtieth review and I claimed I wasn’t going to take forever about these 100 reviews! However … I have been revising a complex novel which my agent is about to start sending out, and I have also written four short stories that I think might be not too bad, so it’s not like I’ve been doing nothing, But I haven’t been reviewing, and that needs to change. So …

“About My Mother” by Tahar Ben Jelloun is my first encounter with this writer who has been ‘regularly’ shortlisted for the Nobel Prize for Literature. My heart opened to him before I read a word of his novel – as a occasionally shortlisted and frequently long-listed writer (although of nothing like his level of acclaim) I’ve experienced the fellow feeling that all literary ‘bridesmaids’ probably endure.

First and foremost, I want to talk about the quality of translation. Ros Schwartz and Lulu Norman appear to me to have done a brilliant job. My French comprehension is solid, my familiarity with Francophone literature of the Maghreb is reasonable and their work read flawlessly to this non-expert.

Second, this book is worth reading, not because it offers a cultural insight (although it does) nor because Ben Jelloun is ‘Morocco’s greatest living author’ (cover quote) but because it’s a painful, moving and rewarding memoir of the loss of a parent to degenerative disease. As such, and as more of us are required to adjust our thinking, and our lives, to the long and often vicious decline of one or more parents, it’s an instructive read, as well as a profound one.

But it’s not straightforward – the narrator, Tahar himself, is elusive and possibly unreliable. At one point he questions whether his parents loved one another, but by the end of the book we’re in little doubt that (a) they didn’t and (b) he knew it all along. Despite this, when it comes to the burial preparations, which he and his brother make long before their mother’s death, he plans to bury her alongside the man she didn’t love, even though he makes a weak joke about them not being happy to be in the same bed again. Is he weak? Is this culturally appropriate behaviour? Does his big brother’s belief that this is the best decision override his doubts? We never find out the reason for his behaviour.

We travel, metaphorically, with Lalla Fatma, Tahar’s mother, as she journeys back to her first marriage, aged 15, to the love of her life who dies before she’s given birth to their only child, a daughter Touria, at just 16 years old. We experience war-torn Fez; we hear the story of Fatma’s second marriage as a second wife, whose husband again dies within months and then as a second wife to a man whose first wife believes her husband is impotent. Fatma succeeds in ousting the first wife when she gives birth to a boy.The third husband’s first wife is repudiated and chooses to marry a butcher and then gives birth to twins.

What a tale – if it’s true. Is it true? The book is described as a novel but the accounts largely seem autobiographical, unsensational, apart from this almost mythic series of marriages.

The question of what to make of the narrative is an understated if pervasive one for the reader. It requires the interior effort that the best fiction regularly provokes. The most evident ‘reality’ is Tahar’s ambivalence over his mother’s carer, Keltum and this domestic perspective is what grounds the novel and gives the reader some certainty about Tahar’s centrality to this tale of a mother’s decline and death.

He wants to like Keltum, he really does. But he can’t, no matter how often he expounds on her good nature, her ability to do what Fatma’s own children can’t, or won’t. He keeps coming back to Keltum’s ill-concealed resentments, her cupidity, the fact that she’s ripping off ‘Lalla’ Fatma – Lalla is a term of respect but Keltum is slyly disrespectful to Fatma and to Fatma’s sons.

Under the dislike of Keltum is a lurking unease – shouldn’t Fatma be in the home of one of her children? While Tahar is happy enough to criticise the old peoples’ homes of Europe, he can’t avoid the fact that Fatma isn’t being cared fro as a respected Muslim parent should be – and there’s an unspoken debate going in between her children: Touria, the daughter of the first marriage who keeps making Hajj, possibly to avoid her responsibilities to Fatma; the oldest son who seems willing to take on death duties but not lifetime care and Tahar himself who visits regularly but seems incapable of considering that his mother really wishes him to install her in his house, or for him to move his own family in with her so Keltum would be unnecessary.

Moving from the immediate to the distant past, from the acutely intimate to the philosophical, this novel performs a fine balancing act. We have no doubt that Tahar loves his mother deeply, but the nature of love and the nature of family are passionately dissected against the backdrop of modern Morocco to reveal the difficulties of accepting death, and the impossibilities of avoiding it.

Layered, complex and indisputably melancholy, this book deserves a wider audience than it will probably obtain. It’s ideal reading for those who are contemplating the decline of a parent or even a partner or friend, for those who relish the perplexities of family life and above all for those who enjoy a more nuanced version of modern Muslim society than is often available through the mainstream media.

Recent Comments